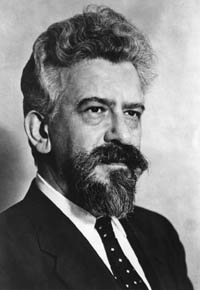

Violin and Melody:

Heschel’s Poetry as “Initiation” of the Ineffable, the Divine

Konstantin Kulakov

For The Philosophical Theology of Abraham Joshua Heschel

Dr. Cornel West

It is difficult to picture the character of Western civilization without the rationalism of Rene Descartes; from the cartesian coordinate graph of mathematics, to the famous "cogito ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am), Descartes looms large in our post-enlightenment thought. Still, from the Foucault’s book Madness and Civilization to Antonio Demasio’s Descartes’ Error, philosophers and neuroscientists have demonstrated the enduring influence and problematical nature of Descartes’s thought. Abraham Joshua Heschel’s philosophy-of-religion begins where Descartes left off, challenging Descartes’ rationalism. For Heschel, “philosophy that begins with radical doubt ends in radical despair.”[1] It is not a comprehensive and coherent system of philosophical propositions that affirm God’s attributes (i.e. Aquinas, Calvin); instead, Heschel argues that philosophy begins in wonder: for him, philosophy is “a retreat, giving up premises rather than adding one, going behind self-consciousness and questioning the self and all its cognitive pretensions.”[2]

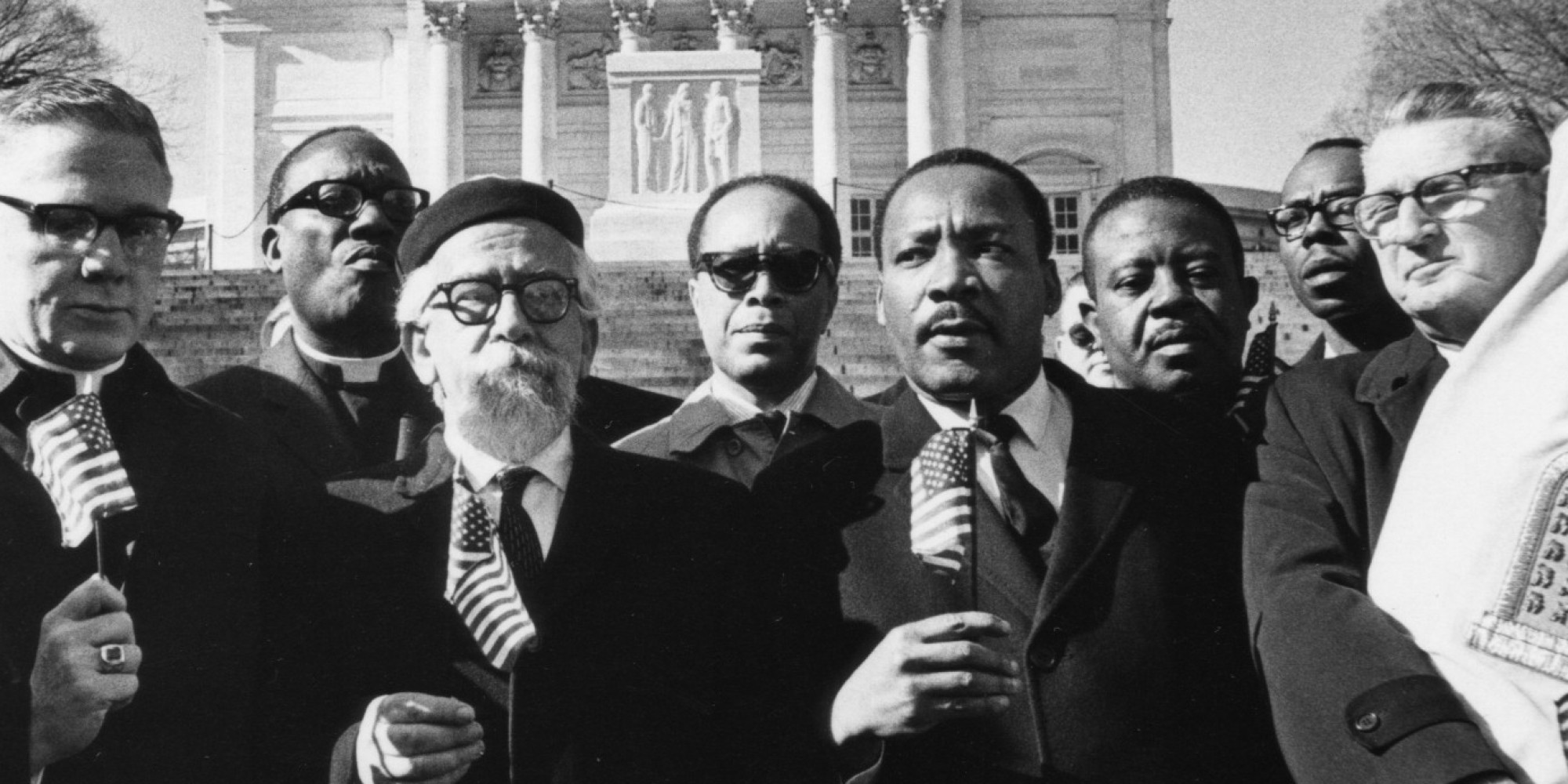

I will never forget a fellow classmate’s response to Heschel’s collection The Ineffable Name of God: Man: “I didn’t like it. I felt that there is something missing there; it does not compare to the fullness of his prose.” However, it is exactly this poetic economy, efficiency of language that defines Heschel’s philosophy of religion. “Music, poetry, religion— they all initiate in the soul’s encounter with an aspect of reality for which reason has no concepts and language has no names.”[3] Along with Heinrich Zimmer, I argue that it is the particularity of poetry that provides a medium where the embodied, complex, and ambiguous nature of reality may be engaged without the reductionist, descriptive impulse. Through poetry, we may encounter the experience of an “activist theology” on its own terms. Thus, it is my assumption that Heschel’s philosophy of religion is inseparable from his poetry just as his theology is inseparable from his activism. Throughout this paper, I will explore three maxims of Heschel’s philosophy of religion and critically examine how his poetry is a reification of each maxim: 1) wonder as the beginning of philosophy, 2) science and spiritual insight as distinct, objective reality 3) and wonder as a call to action.

Wonder as the Beginning of Philosophy

Heschel’s philosophy makes a powerful case for wonder; however, it is only by relating his prose (philosophy of religion) to his poetry may we engage the experience of wonder on its own terms. Heschel writes: “the greatest hindrance to knowledge is our adjustment to conventional notions, to mental cliches.”[4] Heschel already witnessed what he believes to be the logical end of modernity: the instrumental reason of Zyklon B and the atom bomb. Thus, for him, the Cartesian maxim of radical doubt will only lead to radical despair. By affirming wonder, Heschel claims that he is returning to Plato’s conception of thaumatism and disturbing mental placidity. Thus, Heschel does not sever his tie to what he referred to the ineffable. One of the words used to describe the experience of wonder is reverence: “Reverence is an attitude as indigenous to human consciousness as fear when facing danger or pain when hurt. The scope of revered objects may vary, reverence itself is characteristic of man in all civilizations….”[5]

However, by claiming that the essential characteristic of wonder escapes language, Heschel encounters a new problem: the difficulty of all discourse, including poetry, of engaging the ineffable. Heschel addresses this problem through the concept of the indicative, often turning to embodied sensory language of love, beauty and nature: “…while we are unable either to define or to describe the ineffable, it is given to us to point to it. By means of indicative rather than descriptive terms, we are able to convey to others those features of our perception which are known to all men.”[6] Nevertheless, Heschel admits that indicative terms may diverge for different people, but it is the “essence of perception,” the universal capacity that is recognizable.

In order to explore the characteristics of wonder, it is necessary to ground the nature of the experience in the philosophical language of Heschel: “often it appears as if the mind were a sieve in which we try to hold the flux of reality, and there are moments in which the mind is swept away by the tide of the unexplorable, a tide usually stemmed but never receding.”[7] One of the strongest illustrations of this experience is in Heschel’s poem “Need.”

As still as the growing of a hair on me,

A feeling ripens deep in me, truly of You

And feeling Alarm—

I must lead them to words, to screams.

Where can I ferret out Your name […]

I’ll disappear in the night, through the stars and forest—

I’ll be silent.

I’ll scream and wail an alarm:

Haw Aw! Haw Aw!

…

As still as the growing of a hair on me,

A fire ripens deep in me—

I know not from where, I know not at all.[8]

In this poem, there is no need to fit the demands of philosophical categories, premises and conclusions, and soundness of argument; instead, we witness the experience on its own terms. First, it is important to examine Heschel’s broader view of wonder and meaning. For Heschel, “What we encounter in our perception of the sublime, in our radical amazement, is a spiritual suggestiveness of reality, an allusiveness to transcendent meaning.”[9] The line “A feeling ripens deep in me, truly of You / And feeling Alarm—” is relevant: the metaphor of a feeling “ripening” does not fit the accepted abstract psychological terminology. Thus, words are selected based on their dramatic effect as opposed to the precision in regards to scientific standards of judgment. If the experience of the feeling is metaphorized as “ripening,” then the feeling itself has a spiritual, transcendence meaning: organic, life-affirming, spiritual growth. Lastly, the choice of enjambment of “You / And feeling alarm” facilitates a dramatic, evocative experience that is indicative of a transcendent meaning.

In the fifth stanza, we encounter the complex nature of this experience and through its traditionally-non-sensical, paradoxical nature, further pointing to the experience of transcendence: “I’ll disappear in the night, through the stars and forest— “I’ll be silent. / I’ll scream and wail an alarm: / Haw Aw! Haw Aw!” Here, through the equally-affirmed statements of being silent and screaming, Heschel does not satisfy the principle of non-contradiction, but instead subverts it; nevertheless, Heschel is able to illustrate the character of the experience. In many ways, this stanza bears significance to Heschel’s pietism where the stream of consciousness and expletive “haw Aw!” enact the uninhibited drama of humanity’s vexed and transcending relationship to the ineffable God; for it is through this drama that humanity may approach some unexpected solution. In the Hasidism, the solution is in the problem: “There is a strange contradiction in man’s bringing charges in the name of Truth about the absence of Truth; such an argument can be meaningful only if it presupposes the presence of Truth. Is not our agony over the burial of Truth evidence of the life and power of Truth?”[10]

The last stanza is the most clear illustration of the mind sieve that is swept away by the tide of the unexplorable: “As still as the growing of a hair on me, / A fire ripens deep in me— / I know not from where, I know not at all.” The last stanza begins with a repetition of the first stanza. However, there are two changes: 1) the feeling becomes a fire, 2) and the feeling loses its reference point completely. Thus, the experience ends in a strong affirmation of wonder and unintelligibility. Through the affirmation of unintelligibility, there is no immature ignorance, but instead, a wise humility. There is a much deeper phenomena at hand: “The most incomprehensible fact is the fact that we comprehend at all.”[11] This insight is not new to even the community of Anglo-American, analytic philosophers (i.e. philosophers Thomas Nagel and Frank Jackson contribute to the problem of consciousness, defending the qualitative nature of consciousness through qualia).

Science as Legitimate yet Limited

For Heschel, modernity, and natural science in particular, is extensively engaged. However, in his poetry, Heschel does not engage natural science in an explicit way. Nevertheless, by studying the nature of the poetry, one may see how the experiances relate to the philosophy of religion as well as Heschel’s rudimentary philosophy of science. From penicillin to vaccines, automobiles, heart transplants, and Internet technology, natural science has ushered in a reality unimaginable to medieval society. However, natural science also helped usher in 20th century horrors like the atom bomb and Zyklon B as well as contemporary menaces like industrial pollution and drone warfare.

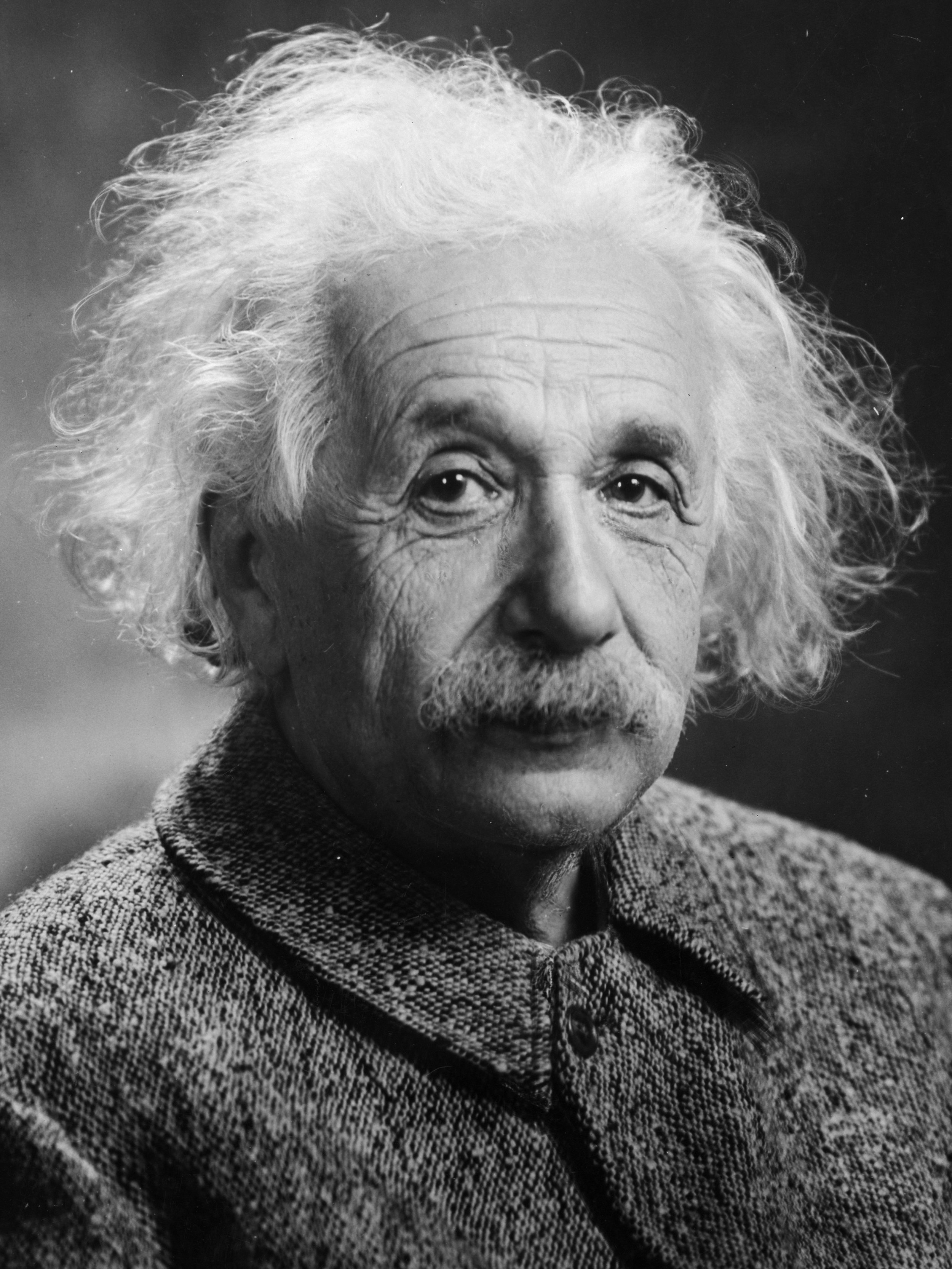

With the towering advancements of Einstein and Watson and Crick, Heschel neither retreated into an anti-scientific literalism of fundamentalists, nor did he believe that science was the only arbiter of objective knowledge: “Science extends rather than limits the scope of the ineffable, and our radical amazement is enhanced rather than reduced by the advancement of knowledge.”[12] In many ways, his writing resonated with the questions opened by the quantum revolution: “Scientific research is an entry into the endless, not a blind alley; solving one problem, a greater one enters our sight…”[13] For example, through the apparatus of the electron tunneling microscope, it was discovered that the more fundamental structure of the universe behaved in laws that contradicted classical mechanics; this only complicated things. Furthermore, for Heschel, the turn to secularize religion in order to fit into the narrow box of positivism was a narrow assumption. For him, the encounter with the ineffable was not reduced to an internal, psychological reality a la Maslow.

Instead, reality possessed meaning, an objective meaning. He wrotes, “namely, that meaning is something which occurs outside the mind in objective things— independent of subjective awareness of it.”[14] Thus, Heschel resisted the epistemological privilege that white liberal Christians and secular humanists gave natural science. Implicitly, this had important implications in regards to power and the oppressed. Even if they were interested in social justice, in promoting their ideology, liberals and secular humanists robbed many minorities of the only spiritual authority they had and raised themselves as the ultimate arbiters of knowledge.

Heschel does not explicitly write of or engage natural science in his poetry. However, I argue that it is precisely Heschel’s philosophy of religion that undergirds such artistic decisions. For Heschel, “reason cannot go beyond the shore, and the sense of the ineffable is out of place where we measure, where we weigh.”[15] Nevertheless, poetry, among other practices, is fit for the encounter: “Music, poetry, religion— they all initiate in the soul’s encounter with an aspect of reality for which reason has no concepts and language has no names.” In other words, it can be said that reason and natural science, which are quantitative, do not engage qualitative reality; and they do not engage this reality because only metaphor, with its evocative qualities, may lead to qualitative dimensions (i.e. transcendence). Heschel’s poem, “The Right to Wonder,” allows us to examine the nature of religious experience and how it may enhance the human situation by encountering the spiritual dimension of erotic love.

Your face—God’s crest—

His scepter—your hands.

It’s your beauty, I know—

gives poets proof of God […]

When I first touched

your endlessly-tender shoulder,

like Heaven itself—

you sweetly sealed

my right to wonder.

Since then I carry you in my ear,

The distant pull of your voice,

and am as if by a thousand holy festivals

enriched.[16]

In these two stanzas, Heschel begins to show the correlational nature of physical reality and spiritual reality; again, this is because, for Heschel, reality possessed meaning, an objective meaning. The woman’s face takes on the objective meaning of divinity. Heschel, as a Jewish humanist, asserts that humans are God’s image on earth. The second half of the stanza, “It’s your beauty, I know— / gives poets proof of God” is a more explicit, even abstractly framed, illustration of the metaphorization of the previous line. The balance between imagery and the speaker’s narration makes a connection to the rational, practical, and empirical world. It could be argued that the word choice “poets” implies that the proof of God is beyond the limits of ordinary empirical science; it is another qualitative dimension: “beauty.”

In the second stanza, we encounter a different empirical reality; here, it is the “endlessly-tender shoulder” that is allusive to the meaning of “heaven itself.” This demonstrates that even the metaphors are correlational as argued in his philosophy of religion; in other words, Heschel asserts that metaphors or “indicative” words may be different, but the “essence of perception” is the same. Thus, it could be argued that for another poet, the face of the woman may become God’s light. Although the metaphor differs, the essential meaning is the same: transcendence.

Finally, the line “you sweetly sealed / my right to wonder” is the counter-point to the imagery and metaphorization before. Again, a more explicit, abstract noun “wonder” and “right” is employed as Heschel connects the imagery to the voice of the speaker. Furthermore, the title and line “right to wonder” is the legitimatization of spiritual “insight.” This is because for Heschel: “Insights are the roots of art, philosophy and religion, and must be acknowledged as common and fundamental facts of mental life.”[17] Lastly, it is important to address exactly how Heschel resisted the anti-scientific literalism of fundamentalists. The answer can be found in the context of his philosophy of religion. As opposed to employing scientific claims in his poetry, Heschel demonstrated that practices that “initiate the soul’s encounter with the sublime” are not even empirical claims. They are qualitative claims. In a time when scriptural texts were interpreted in literal, anachronistic methods, Heschel resisted this by reading scripture as spiritual insight and making claims that did not trespass unto the field of science, but opened one to the spiritual significance of reality.

Wonder as a Call to Action

For Heschel, wonder did not lead to complacency or asceticism, but to obligation and action. This theme is powerfully illustrated by Heschel’s poetry. First, in the section, What to do With Wonder, he writes: “The world consists, not of things, but of tasks. Wonder is the state of our being asked. The ineffable is a question addressed to us.”[18] In Moral Granduar and Spiritual Audacity, Heschel writes: “This is no time for neutrality. We Jews cannot remain aloof or indifferent. We, too, are either ministers of the sacred or slaves of evil…” We may ask how wonder may lead to a sense of responsibility, but we are missing something: For Heschel, the entire universe had a spiritual significance. As he wrote, “To be implies to stand for, because every being is representative of something that is more than itself; because the seen, the known, stands for the unseen, the unknown.” In the following poem, I and You, Heschel presents the most direct image of human-divine inseparability:

I and You

Transmissions flow from your heart to Mine,

trading, twining My pain with yours.

Am I not—You? Are you not—I?

My nerves are clustered with Yours.

Your dreams have met with mine.

Are we not one in the bodies of millions?

Often I glimpse Myself in everyone’ form,

hear My own speech—a distant, quiet voice—in people’s weeping,

as if under millions of masks My face would lie hidden.

I live in Me and in you.

Through your lips goes a word from Me to Me,

From your eyes drips a tear—its source in Me.

When a need pains You, alarm me!

When You miss a human being

tear open my door!

You live in Yourself, You live me.[19]

One of the most striking features of this poem is the unexpected shifts in speaker. The shifts are suggested by the capitalization of “You” and “Me.” In the first stanza, the speaker appears to be God because “Mine” is capitalized; however, in the last line of the stanza, suddenly “You” becomes capitalized indicating that the speaker is human. This interchangebility is punctuated by the statement “Am I not—You? Are you not—I?” In the second stanza, this interchangeability is expanded from the micro individual/God relationship to the macro humanity/God relationship: “Are we not one in the bodies of millions?” In the stanzas following, the texture of this is reified in the imagery of tears: “Through your lips goes a word from Me to Me, / From your eyes drips a tear—its source in Me.”

The interchangeability and inseparability is not only a spiritual meditation, but a call to action. As Heschel asserts, “The world consists, not of things, but of tasks.” In light of the inseparability of God and humanity, liberalist individualism is impossible: love thy neighbor as yourself is reified, flesh and bone. First, if a tear drop falls from the cheek of any “disparate” human being, that tear drop is God’s. Second, if a tear-drop falls from the cheek of any “disparate” human being, it is also “the bodies of millions.”

Given poetry’s qualitative dimension, we are not only compelled to treat each other with respect by logical necessity. In other words, it is not only the ontological connection which is presented, but the experiential, evocative connection. The embodied imagery of a tear compels one to feel the suffering of others and such an emotional sensibility and worldview makes demands on humanity. This is why the last stanza includes these exclamatory lines: “When a need pains You, alarm me! / When You miss a human being / tear open my door!”

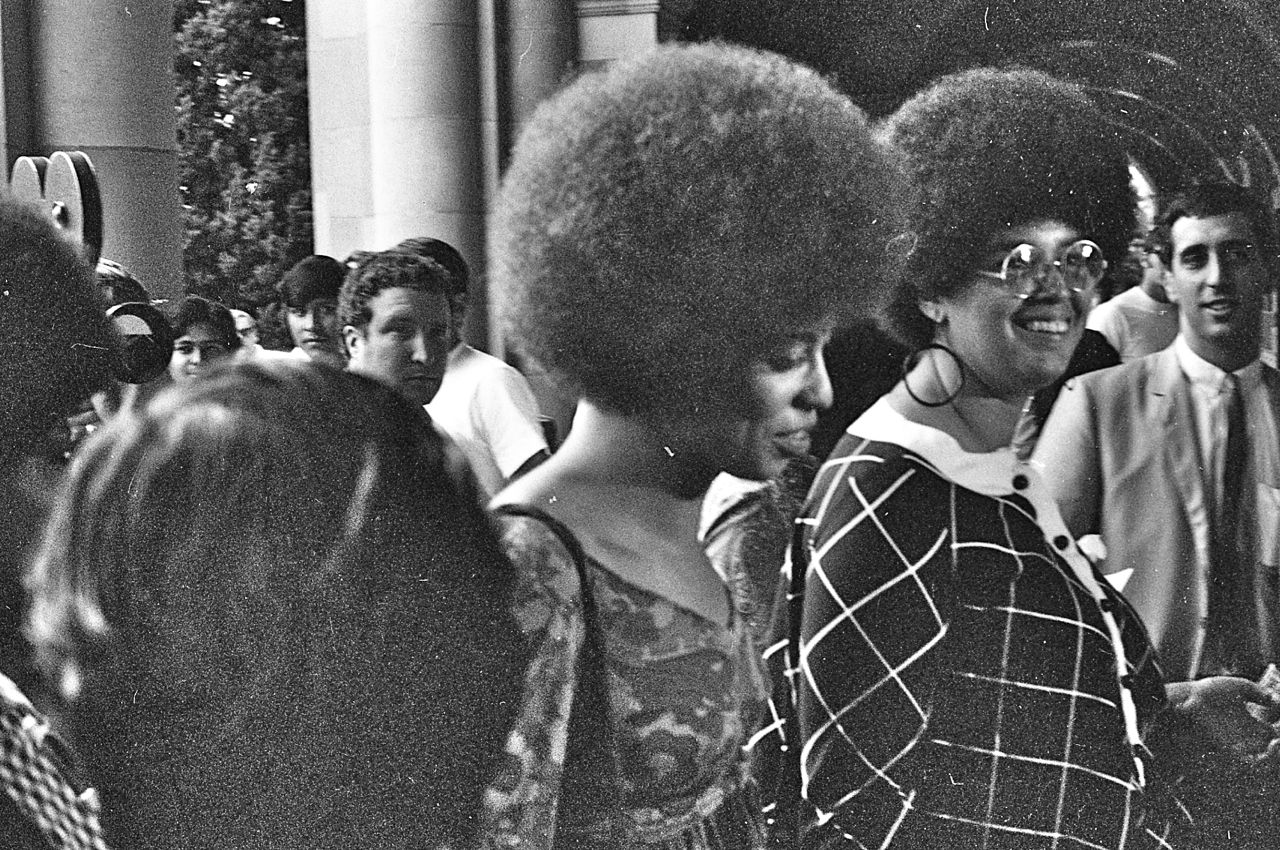

Today, the US holds military presence in a 150 countries with 172,966 active-duty personnel.[20] By strongly supporting tyrannical states like the Saudi Royal family, it robs Saudi citizens of basic freedom and refuses to participate in the international criminal court. Israel is now the closest alley to United States, supporting every invasion and expanding settlements against international law. Domestically, as documented in Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow, the United States holds the highest incarceration rate: 2.3 million prisoners with blacks and Hispanics accounting for 60% of the inmates. To struggle for justice during Heschel’s time was to choose life, to oppose explicit laws rejecting the humanity of others. But American racism has changed from explicit to hidden, an ugly systemic rejection of black lives.

During his life, Heschel confronted the injustices of his day head-on at their root from prose to poetry. As thinking and feeling creatures with a capacity for beauty, the fulllness of life's picture, the question is how will we address these injustices of today and does our philosophy of religion, religious body, and culture (poetry, visual, film) urgently demand it.

[1] Abraham Joshua Heschel, Man Is Not Alone: A Philosophy of Religion, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition), Kindle Location 289.

[2] Ibid, Kindle Locations 1068-1070.

[3] Ibid, Kindle Locations 537-538.

[4] Ibid, Kindle Location 265.

[5] Ibid, Kindle Location 401.

[6] Ibid, Kindle Location 377.

[7] Ibid, Kindle 232.

[8] Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Ineffable Name of God: Man, (New York: Continuum Books, 2007), 63.

[9] Abraham Joshua Heschel, Man Is Not Alone: A Philosophy of Religion, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition), Kindle Location 385.

[10] Abraham Joshua Heschel, A Passion for Truth, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973), Kindle Locations 3796-3797.

[11] Abraham Joshua Heschel, Man Is Not Alone: A Philosophy of Religion, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition), Kindle Location 305.

[12] Ibid, Kindle Location 305.

[13] Ibid, Kindle Location 437.

[14] Ibid, Kindle Location 439.

[15] Ibid, Kindle Location 252.

[16] Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Ineffable Name of God: Man, (New York: Continuum Books, 2007), 107.

[17]. Abraham Joshua Heschel, Man Is Not Alone: A Philosophy of Religion, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kindle Edition), Kindle Location 341.

[18] Ibid, Kindle Location 884.

[19] Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Ineffable Name of God: Man, (New York: Continuum Books, 2007), 31.

[20] "Total Military Personnel and Dependent End Strength By Service, Regional Area, and Country". Defense Manpower Data Center. September 30, 2014.